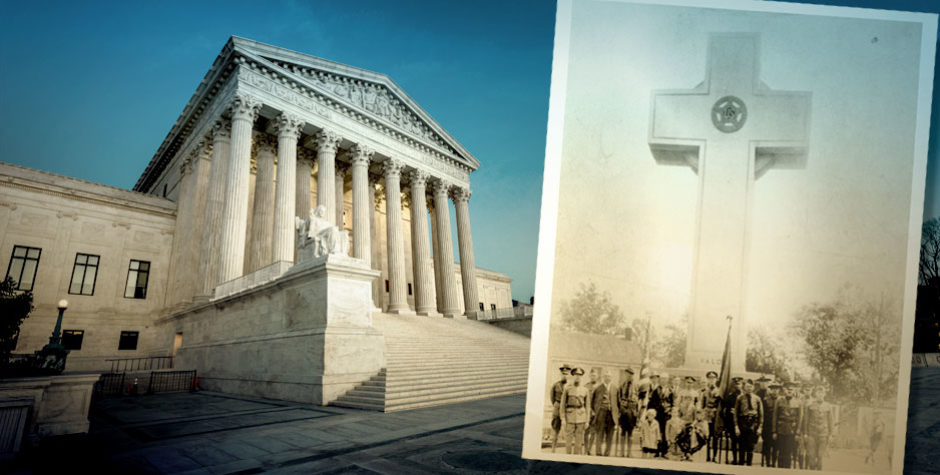

ACLJ Files Supreme Court Brief in Support of Bladensburg Peace Cross

Does a near-century-old memorial cross, dedicated to the memory of local soldiers who perished in World War I, violate the First Amendment’s prohibition against governmental establishment of religion?

As we point out in an amicus curiae brief filed with the Supreme Court today, the answer to that question is an unequivocal no.

As explained here and here, the Bladensburg World War I Veterans Memorial, often called “the Peace Cross,” was erected nearly one hundred years ago for the purpose of honoring forty-nine men from Prince George’s County, Maryland who served their country during the Great War.

The forty-foot tall cross, surrounded by other monuments memorializing armed conflicts, does not proselytize, evangelize, or proclaim the Christian faith as a government-sanctioned religion. It does not coerce citizens into participating in a religious exercise or practice.

One need not look beyond the memorial itself to understand the important civic role the Peace Cross serves. On the pedestal of the monument is a bronze plaque that reads:

THIS MEMORIAL CROSS

DEDICATED TO THE HEROES

OF PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY, MARYLAND WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN

THE GREAT WAR FOR THE LIBERTY OF THE WORLD

Inscribed at the base of the monument are four words: “VALOR, ENDURANCE, COURAGE, and DEVOTION.”

Also written on the monument is a statement from President Woodrow Wilson’s request for a declaration of war: “The right is more precious than peace. We shall fight for the things we have always carried nearest our hearts. To such a task we dedicate our lives.”

The fact that the Bladensburg memorial was created in the shape of a Latin cross poses no Establishment Clause problem. As we point out in our amicus brief, quoting from an opinion by Justice Kennedy, the last time the Supreme Court considered a cross memorial:

a Latin cross is not merely a reaffirmation of Christian beliefs. It is a symbol often used to honor and respect those whose heroic acts, noble contributions, and patient striving help secure an honored place in history for this Nation and its people. . . . It evokes thousands of small crosses in foreign fields marking the graves of Americans who fell in battles, battles whose tragedies are compounded if the fallen are forgotten.

In short, the idea that the Peace Cross constitutes an “establishment of religion” is just plain wrong. A correct and historical understanding of the Establishment Clause prohibits the government from coercing its citizens into directly supporting a church through taxation, or mandating church attendance or worship. It does not prohibit the government from public displaying a symbol that partakes of both the secular and the religious. As the late Chief Justice Rehnquist once wrote, “Simply having religious content or promoting a message consistent with a religious doctrine does not run afoul of the Establishment Clause.”

Another issue in this case the Supreme Court needs to correct is what’s commonly known as “offended observer” standing. Under that theory, a court has the authority to decide a challenge to a public display based on nothing more than that observation of the display causes offense, hurt feelings, or ideological objection. Groups like the American Humanist Association, the ACLU, and the Freedom from Religion Foundation have used this theory to challenge everything from nativity scenes, to Ten Commandments displays, to memorial crosses, like the one at issue in this case.

The critical problem with “offended observer” standing, as we point out in our amicus brief, is that it is inconsistent with Article III of the U.S. Constitution. Article III mandates, among other things, that federal courts only rule upon cases or controversies. This means, first and foremost, that the party bringing a case to federal court must be injured in some way. Without an injury, there can be no case; without a case, there can be no decision.

The Supreme Court has consistently held that mere ideological disagreement with government action does not rise to the level of an injury for Article III purposes. Plaintiffs in such cases, according to the Court in a 1982 Establishment Clause decision,

fail to identify any personal injury suffered by them as a consequence of the alleged constitutional error, other than the psychological consequence presumably produced by observation of conduct with which one disagrees. That is not an injury sufficient to confer standing under Art. III, even though the disagreement is phrased in constitutional terms.

Limiting the power of the courts to resolving real injuries, instead of adjudicating feelings of offense, makes perfect sense. If one could file a federal lawsuit against the government based on disagreement or offense alone, the courts would be inundated with cases brought by upset and aggrieved citizens. As one federal judge correctly put it, “there would be universal standing: anyone could contest any public policy or action he disliked.” Political and ideological disagreements should be fought out in the legislatures, not the federal courts.

In this case, the Peace Cross challengers allege only that they are offended by the cross and object to its presence on public property. In other words, they have suffered no Article III injury—only that they are “offended observers.” It’s time for the Supreme Court to put an end to federal courts deciding cases based on such allegations.

As we conclude in our brief:

Federal courts do not have jurisdiction to entertain challenges by individuals merely offended by government actions or displays that they do not like as an ideological or religious matter. There should be no different rule for challenges brought under the Establishment Clause. This Court should make that clear in this case.

Finally, we are honored that Lieutenant General Robert R. Blackman, USMC (Ret.), has joined us on this brief as a friend of the Court. Lt. Gen. Blackman was commissioned into the Marine Corps from Cornell University in 1970. Among other key assignments over 37 years of active service, Lt. Gen. Blackman served as Chief of Staff of the Coalition Forces Land Component Command during Operation Iraqi Freedom; Commanding General, III Marine Expeditionary Force; and Commander, Marine Corps Forces Command. After leaving active service, Lt. Gen. Blackman served with the Marine Corps’ Marine Air-Ground Task Force Training Program and Joint Warfighting Center advising and mentoring operational commanders and staffs. Lt. Gen. Blackman has served as President and CEO of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation since March 2011 and will retire at the end of this year.

In addition, we filed this brief on behalf of more than 230,000 of our ACLJ members who signed on to our Committee to Defend the Cross and Honor Heroes.

We will keep you posted as the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in this case and issues its ruling by the end of June 2019.